[Note: Below is a new paper discussing a Pescatarian Diet. How much of it was generated by an agent?]

A pescatarian diet is essentially a vegetarian diet that also includes fish and seafood. In practice, pescatarians eat plenty of plant-based foods—such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds—often along with eggs and dairy, plus fish and shellfish as primary protein sources. Pescatarians do not consume red meat or poultry. This eating pattern has grown in popularity in recent years; about 3%–4% of adults in the United States identify as pescatarian. Health is a major motivator for many, as a pescatarian diet offers a balance of the benefits of plant-based eating with the additional nutrients and variety provided by seafood.

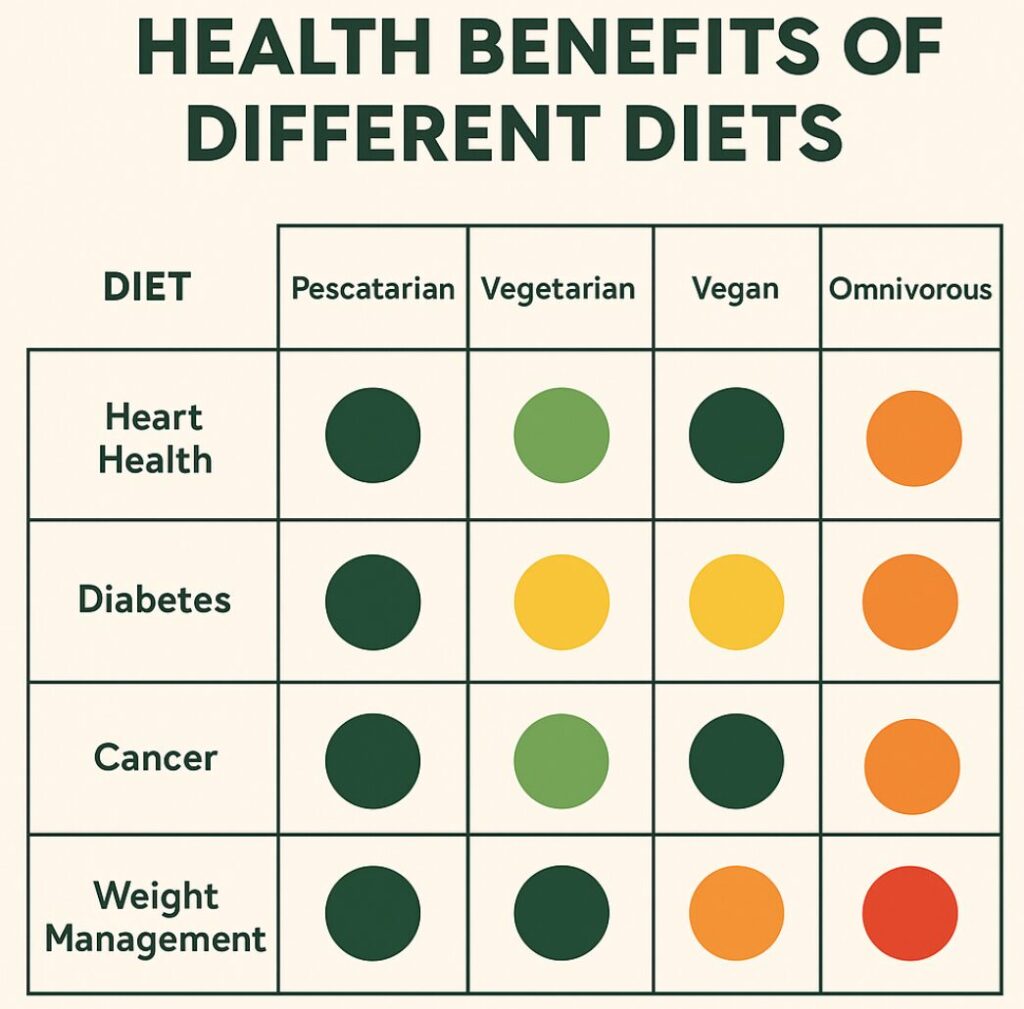

In this post, we will focus exclusively on the health aspects of a pescatarian diet. We’ll examine its nutritional profile and discuss how it compares to vegetarian, vegan, and omnivorous diets in terms of nutritional adequacy, disease prevention, longevity, weight management, and cardiovascular health. Recent scientific findings from peer-reviewed studies and authoritative sources will be cited throughout to provide an evidence-based perspective. The goal is to give health-conscious readers a comprehensive, up-to-date look at the potential health benefits of choosing a pescatarian dietary pattern.

… we are now Shifting gears from agentic content.